The last few minutes have seen a startling justaposition in my news feed, in quick succession I heard:

- On BBC Radio 4’s The World at One there was coverage of the 75th anniversary of D-day, with a reminder of the seriousness of the task and the sheer amount of support from other countries that enabled this to succeed, which flatly contradicts the idea that “the UK won the war” in it’s own strength.

- A video from Russia Today showed both Boris Johnson and Jeremy Hunt advocating leaving the EU with no deal — immediately followed by a commentator pointing out the damage that’s already happened and how much worse “No deal” would make things.

- Also on The World at One was a tiny comment about Rory Stewart (also pitching to become Tory leader) explaining that it is crazy to imagine that the EU will re-open negotiations, or to think there is money for drastic tax cuts.

- I’m slowly working my way through the Hindu epic the Mahabharata, as serialised on Indian television, and caught a moment where two mothers whose sons are on opposite sides in the war at the heart of the story console each other. One asks the other whether she will pray for victory: she doesn’t want to force the choice on God who has to disappoint one of them if they both pray for this.

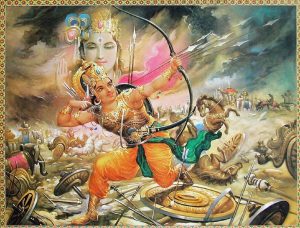

The Mahabharata

The Mahabharata is a rich and multi-layered epic. An irresistable sequence of events push two sets of cousins, the Pandavas and the Kauravas into a war. Last September I blogged about the seeming inevitability of disaster in this story as a way of thinking about the way Brexit was heading.

I am deliberately going through this slowly, savouring the journey of the Mahabharata. The Kurukshetra war is huge and bloody. In people’s responses to it are rich material around making sense of the big questions of life and death, of fate, of attachment and of reincarnation. I’ve just watched the agonised episode where Arjuna’s teenage son Abhimanyu has been killed in a way that seems to violate the rules of war. The grief is searing.

In the royal palace at Hastinapur, Kunti, mother of the Pandava brothers is unable to sleep, overwhelmed by sadness even without yet knowing of her grandson Abhimanyu’s death. She is being consoled by Gandhari, mother of the Kauravas. Both women are suffering as the death toll mounts. Gandhari suggests that they should both pray for each other’s sons: with sadness Kunti points out that this puts God in an impossible position. The Kurukshetra war is sometimes cast as a conflict of truth and untruth: that feels like an enormous over-simplification.

Here are people bound up in oaths, curses, boons and realities that limit them. The incident when Abhimanyu dies looks bad, but one of his assailants had received a boon that he would triumph over four Pandavas: at that moment in the battle, Arjuna was not to hand, and the boon left his brothers powerless. Some versions of the story relate that Abhimanyu was the son of the moon god, who had agreed to let him become incarnate only for 16 years, also making his early death inevitable. But the grief is real. It’s about people caught up in messy reality and finding wholeness in it, despite the suffering, rather than evading it.

The force that drives the Kauravas away from peace is often described as the arrogance, intransigence, ego and vanity of crown prince Duryodhana. It’s not that he is a bad character, but it is that he’s unable to resist the forces of blind ambition in which he is caught up.

Legacy of the Second World War

The genius of the Schuman declaration that led to the forming of the European Coal and Steel Community, which has grown into the EU, was that coal and steel were the raw materials of mid twentieth century warfare. Treaties can be broken, but integrating those industries made war impossible. Like the wisdom that lies behind the Mahabharata this recognises that disagreements will happen and human frailty will show itself, and provides a way for this to end up discussion rather than on the battle field.

Tory leadership

Against this, it feels as if lots of what I am hearing from the Tory leadership campaign is absolutely about ego and vanity.

There are candidates bluffing that they can get a better deal from the EU than Theresa May — though Dominic Raab, as a former Brexit Secretary might have trouble explaining why he didn’t do this in that role, and Michael Gove and Boris Johnson might have done something in Cabinet if this were as easy as they claim.

We have bluff and bluster about “no deal”, as if re-assuring people that it will be fine means that it will. There’s even the fantasy that this threat will make the EU move, on the grounds that “no deal” harms the EU, though, given that “no deal” would do much more harm to the UK, I wonder how on earth the EU is supposed to negotiate with a leader willing to do serious harm to their own country.

There’s also bluff about the Irish border, as if an Irish question that has dogged British politics for well over a century can suddenly be solved, and demands for the restoration of a sovereignty that was never lost (but might well be compromised by Brexit putting us at the whims of China and the US).

Mahabharata: 1

With the honourable exception of Rory Stewart, this feels as if fantasy and untruth is everywhere. One of the insights of the Mahabharata is that untruth can easily come to the fore, often for seemingly-obvious reasons. Good people can still get trapped in webs of it. The human cost is very high, even if those at the heart of untruth seem unable to stop.

Mahabharata: 2

There is a saying that people in the Indian service in the days of the British Empire were advised to read the Mahabharata in order to understand India. In days gone by, people could have imagined a superiority over the Indians. Maintaining that has always needed a failure to recognise reality, but this year (2019) the Indian economy is likely to outstrip that of the UK.

In its timelessness, the Mahabharata offers a way to make sense of human frailty and the human capacity to act unwisely. The commemoration of D-Day is a reminder of how bad this can get. An eye on the richness of another culture puts the immediate and irrational intensity of Brexit in perspective. From where I am sitting, the wisdom and patience on show in the Mahabharata makes the egotism, irrationality and fantasy-chasing of Brexit look juvenile. It’s a reminder that the economic rebalancing in the world at the moment is about countries like India coming out of poverty. Rather than chasing a fantasy of British (or English) superiority, we need to recognise that this change is just and find a way to operate within a multilateral system that works by consensus. That sounds remarkably like the EU.

And in the Mahabharata, the point where the Kurukshetra war becomes inevitable is when the five Pandava brothers ask Duryodhana to return their kingdom. He refuses, and refuses again when they compromise down to five villages, or just five houses. His arrogance and his egotism leads to him losing all on the battlefield.